Huldah's Exile

Part 2

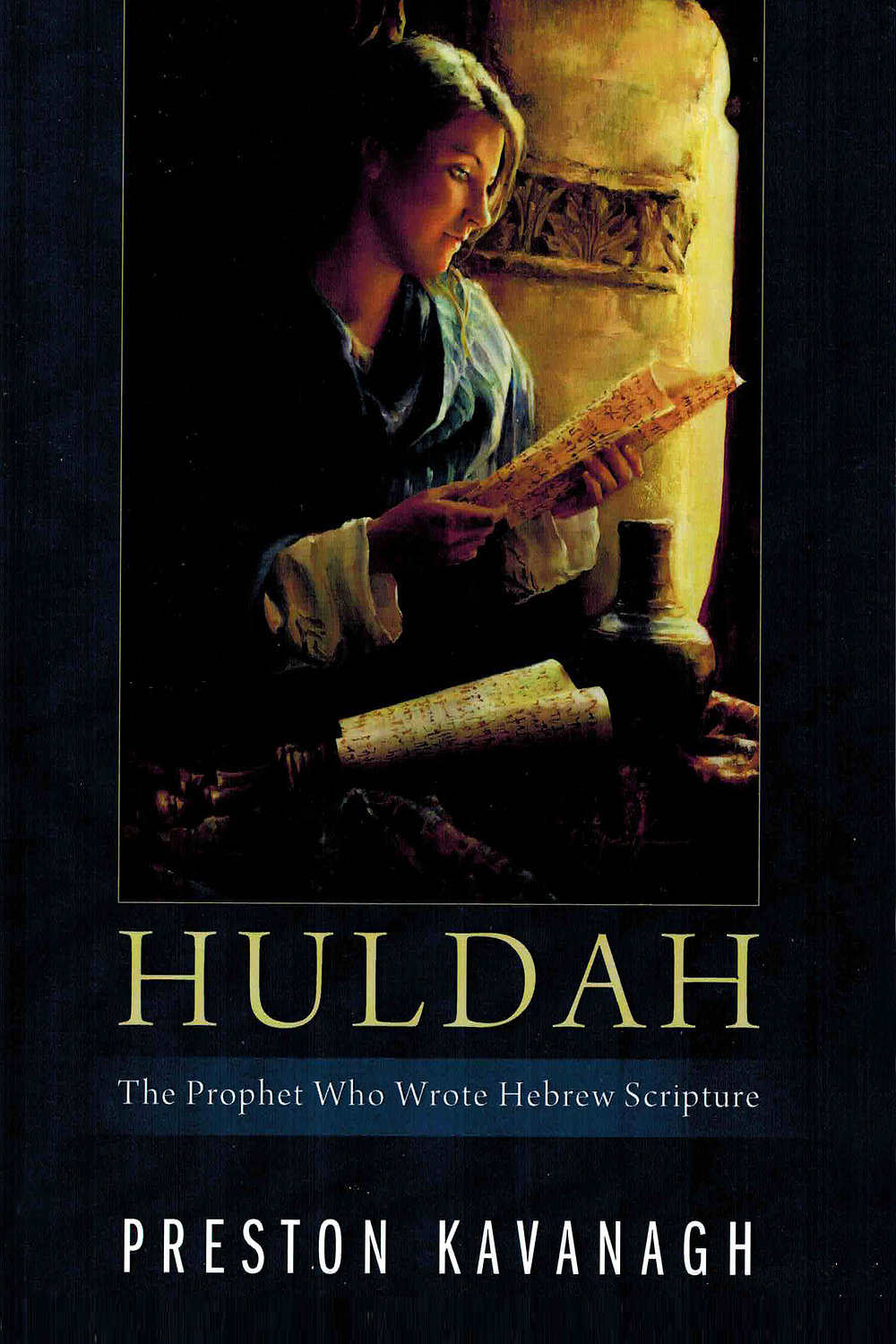

excerpted from Huldah by Preston Kavanagh

This chapter will complete the biography of Huldah the prophet, starting with her exile to Babylon in 597 BCE. For the reader’s convenience, the previous chapter’s table showing Huldah’s life is included below. The last chapter covered the shaded events. This chapter will discuss things yet to come, which are shown without shading on this table.

| Year | Age | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 640 | Birth | |

| 622 | 18 | Consults on temple scroll |

| 615 | 25 | Marries Jehoiakim, bears Jehoiachin |

| 605 | 36 | Sees King Jehoiakim burn prophecy |

| 597 | 43 | Becomes queen mother |

| 597 | 43 | Exiled to Babylonia with Jehoiachin |

| 592 | 48 | As elder in Babylonia visits Ezekiel |

| 586 | 54 | In Jerusalem during siege |

| 586 | 54 | To Mizpah after Jerusalem’s fall |

| 585 | 55 | Gedaliah murdered, Huldah to Egypt |

| 575 | 65 | Cyrus revolt begins |

| 574 | 66 | Israelites take Jerusalem |

| 573 | 67 | Enemies retake Jerusalem, Huldah flees |

| 572 | 68 | Makes way to Bethel |

| 564 | 76 | Death |

597–585: MIDDLE-AGED HULDAH EXILED, NEXT IN BESIEGED JERUSALEM, THEN TO MIZPAH

In 597, Huldah as queen mother accompanied her son Jehoiachin on his journey into exile in Babylonia. A passage from Samuel may report this event: “So the king left, followed by all his [H, Jehoiachin] household, except ten concubines whom he left behind [Jehoiachin] to look after the house. The king left, followed by all [H, Jehoiachin] the people; and they stopped at the last house” (2 Sam 15:16–17). Ostensibly, this text is about King David; for knowing readers, how-ever, the cluster of anagrams steers it to the 597 departure of Huldah and Jehoiachin for Babylon. Another text names Jehoiachin and identifies Huldah through anagrams and with the words “king’s mother.” Here is the passage: “He carried away all Jerusalem, all the officials, all the warriors [H, Jehoiachin], ten thousand captives . . . He carried away Jehoiachin to Babylon; the king’s mother, the king’s wives . . . The king of Babylon brought captive to Babylon all the men of valor [H, Jehoiachin]” (2 Kgs 24:14–16).

During her stay in Babylon, Huldah must have attended Nebuchadnezzar’s court and apparently was free to visit the Judeans’ exilic settlements. Undoubtedly she composed scripture, perhaps in collaboration with Judean court officials exiled with the young king. Anagrams provide a glimpse of her and other dignitaries visiting the prophet Ezekiel. His chapter 8 bears the exact date of September 17, 592 BCE. The opening line of that prophecy says, “As I sat in my house, with the elders [H, Cyrus, Baruch] of Judah sitting before me, the hand of the Lord GOD fell upon me there” (Ezek 8:1). A series of visions of idolatry in the Jerusalem temple follows, and the first of them contains another Huldah anagram (Ezek 8:2). The word “elders” in Ezek 8:1 contains anagrams not only for Huldah but also for Cyrus and Baruch. Because 592 is far too early for Cyrus the Great to have been attending meetings (he might have been six years of age), the preface to Ezekiel 8 must have been inserted by an editor, probably Huldah herself. The Cyrus question aside, what we have is her eyewitness account of the meeting. Something else is of interest—Baruch also was there. He was Jeremiah’s able and trusted scribe. Scripture records that Baruch accom-panied that prophet to Egypt in about 585, yet seven years earlier, in 592, he was in Babylonia.

Evidence testifies that Huldah edited the book of Ezekiel. It contains fifteen specific dates, a feature that is unique to the prophet—and important for estab-lishing the chronology of Huldah. Six of those fifteen dates contain Huldah anagrams—for example: “In the seventh year, in the fifth month, on the tenth [H, Jehoiachin] day of the month . . .” and “In the twenty [Jehoiachin]-seventh year, in the first [H] month . . .” (Ezek 20:1; 29:17). Evidence discussed elsewhere indicates that Ezekiel died as a substitute king early in 569. If Huldah edited the book of Ezekiel, she would have done so at Bethel prior to her death in 564. If she were the editor, she would have used her own knowledge or that of acquaint-ances to assign dates that included Huldah anagrams. According to anagrams, Huldah as an elder met with Ezekiel in Babylonia in 592.

Anagrams also show that six years later, in 586, Huldah was back in Jerusalem when Nebuchadnezzar laid siege to the city. The Second Kings account reads, “. . . in the ninth year of his reign, in the tenth month [H, Jehoiachin] . . . Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon came, he and all his army, against Jerusalem, and encamped against it” (2 Kgs 25:1). Thus, when the siege began, Huldah was in Jerusalem. It is not clear whether Jehoiachin accompanied her. Evidence establishes that the young king resided in Babylon in 592. It is surprising to find Huldah back in Jerusalem, but would she have returned there without Jehoiachin? Upon reflection, Huldah as queen mother would never willingly have separated herself from her royal son. But evidence from this book’s final chapter will indicate that Jehoiachin had been imprisoned for an unknown reason earlier than the 560s, when Scripture says he was freed from jail (2 Kgs 25:27).

But why did the authorities allow Huldah—with or without her son—to leave? Almost certainly the Babylonians kept track of the families of their puppet kings, and probably they required them to be at court from time to time. But perhaps Huldah’s masters sent her to Jerusalem because—with good reason—they distrusted their vassal, King Zedekiah. He, of course, was in the process of allying Judah with Egypt against Babylon.

This possibility moves toward likelihood because Jeremiah was in the same anti-Egypt pro-Babylon camp. After Jerusalem fell, Nebuchadnezzar’s chief lieutenant Nebuzaradan went out of his way to spare the prophet, offering Jeremiah his choice of staying in Judah or going to Babylon as a free person (Jer 39:11-14). Huldah coded spellings indicate that Nebuzaradan gave Huldah a similar choice.

Although the author of 2 Kings 25 was parsimonious in using Huldah coded spellings, he or she did it to good effect. The italicized portion shows the ten text words that carry a single coded spelling of Huldah-the-queen-mother. Separately, the italics highlight yet another Huldah anagram. Both techniques confidentially announce that Huldah escaped deportation. “Nebuzaradan the captain of the guard carried into exile . . . all the rest of the population. But the captain of the guard left some of the poorest people of the land [Huldah-the-queen-mother coding] to be vinedressers and tillers of the soil [H]” (2 Kgs 25:11–12).

Where did Huldah go after Nebuzaradan released her? Again, coded Huldah-the-queen-mother spellings provide the answer. The text hiding three consecutive encodings of that compound is italicized: “. . . at Riblah in the land of Hamath. So Judah went into exile out of its land. He appointed Gedaliah son of Ahikam son of Shaphan as governor over the people who remained in the land of Judah, whom King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon had left” (2 Kgs 25:21–22). As the new governor, Gedaliah certainly was sympathetic to his own grandfather Shaphan and to what remained of the circle of Josiah-era reformers. Anagrams show that Nebuzaradan also reprieved Baruch, Ezra (the author of the P Source), and Jacob.

585: AT FIFTY-FIVE, HULDAH FLEES TO EGYPT

Unfortunately for Huldah and the others, Governor Gedaliah did not govern for long. Within a year or so of his appointment, an agent of neighboring Ammon assassinated him. To avoid Babylonian reprisal, Huldah and others at Mizpah fled to Egypt. The time was early in 585, and Huldah would have been fifty-five. It is certain that she was on her way to Egypt by March 3 of 585. On that date, Ezekiel prophesied the doom of Pharaoh at the presumed hand of Babylon. But the prophecy (Ezekiel 32) is at least as much an attack on Huldah as it is on Pharaoh. The prophet, writing from Babylon, marshaled sixteen anagrams against Judah’s queen mother.

Sixteen is a lot—no chapter in Scripture has more. This example contains five of those Huldah anagrams: “all of them uncircumcised [H], killed by the sword . . . for they spread terror in the land of the living. And they [H] do not lie with the fallen warriors [H, Jehoiachin] of long ago who went down to Sheol . . . for the terror of the warriors [H, Jehoiachin] was in the land of the living. So you shall . . . lie among the uncircumcised [H] . . .” (Ezek 32:26–28). The Jehoiachin anagrams imply that Jehoiachin left his Babylonian prison and made his way to Egypt to join other exiles there.

Ezekiel 32 is rich in information. First, Huldah is looking toward a Babylonian invasion of Egypt and pictures Jehoiachin as a warrior (“the mighty”). Also, she draws Ezekiel’s anger because she sides with Egypt rather than Babylon. Furthermore, based on this chapter’s new coding information, scholars can now firm up the year of Gedaliah’s murder. Scripture says that he was assassinated “in the seventh month” (Jer 41:1), which by our calendar was October. We know that Huldah and others were in Judah in October of an unstated year and in Egypt by March 3, 585—five months later—when Ezekiel dated his own chapter that condemned both Pharaoh and Huldah. In conclusion, readers can safely assume that 586 was the year of Gedaliah’s assassination.

585–575: FROM FIFTY-FIVE TO SIXTY-FIVE, HULDAH IN EGYPT

Huldah remained in Egypt for almost a dozen years. A single chapter from the book of Jeremiah proves her presence. Jeremiah 44 is twice as long as most OT chapters and is awash in Huldah coded spellings. The carefully wrought text contains 171 of them—variations of Huldah, Huldah-the-prophetess, Huldah-the-queen-mother, and Huldah-the-wife-of-Shallum. The author has concealed at least one encoding under twenty-eight of the chapter’s thirty verses, and the total of Huldah encodings eliminates coincidence.

Jeremiah addressed his words to exiles living in locations at the eastern edge of the Nile’s delta and in Upper (southern) Egypt. The prophecy declares that God had desolated Judah because its people had made offerings to other gods. And despite this lesson, those who had escaped to Egypt had resumed their detestable practices. Jeremiah spoke heatedly of worship of the queen of heaven—worship that apparently had a large female following. As a result of this worship, those who had fled to Egypt would never be able to return to Judah. Instead, they would perish in Egypt by famine, pestilence, or the sword. Jeremiah 44 records an actual debate between the prophet and Huldah’s followers—perhaps even Huldah herself. It took place in Pathros, which was the area of Upper Egypt between modern Cairo and Aswan.

Jeremiah’s own words show that both husbands and wives vehemently rejected Jeremiah’s arguments. They said, “We will . . . make offerings to the queen of heaven and pour out libations to her, just as we and our ances-tors, our kings and our officials, used to do in the towns of Judah . . . We used to have plenty of food, and prospered, and saw no misfortune. But from the time we stopped making offerings to the queen of heaven and pouring out libations to her, we have lacked everything . . .” (Jer 44:17–18).

Huldah probably led the debate against Jeremiah, because the chapter’s heaviest Huldah coding lies beneath the words quoted above. Both sides argued their own interpretation of recent Judean history. King Manasseh had established worship of female deities, Josiah had excised them, and Jehoiakim and Zedekiah had reinstituted them. After the Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem, those who fled south reestablished the cult.

Worship of the queen of heaven in Egypt apparently was transplanted from Jerusalem (see Jer 7:17–18), though it has not been identified elsewhere in the ANE. It probably combined features of several fertility goddesses—including the Asherah—and could even have included a female companion for Yahweh. There is evidence that “before the reforming kings in Judah, the Asherah seems to have been entirely legitimate.” Jeremiah said that exiles—especially wives—who had resumed their impure worship in Egypt would perish. Those in Egypt countered that when they stopped such practices, bad things commenced to happen, but that since they had resumed that worship, things were going well. Jeremiah’s final word was that God was going to watch over the exiles for bad and not for good. They would indeed die. Kathleen O’Connor notes that Jeremiah accused wives alone of false worship while the offense of their husbands was reduced to failing to control their wives.

And where was Huldah in this? Given Jeremiah’s heavy encoding of Huldah in Jeremiah 44, she probably was at the center of the dispute. When Huldah presided in Jerusalem as Jehoiachin’s queen mother, we know from Jeremiah himself that she had a throne and wore a diadem. The Lord told Jeremiah to declare, “Say to the king and the queen mother [H, Jehoiachin]: ‘Take a lowly seat, for your beautiful crown has come down from your head’” (Jer 13:18). Huldah certainly had the authority to be chief patron of the Asherah worship in Jerusalem before her exile. Further, the heavy Huldah coding in Jeremiah 44 indicates that she was deeply involved in the queen of heaven cult a few years later in Egypt.

Huldah and Jeremiah were the same age and both grew up in or near Jerusalem. Tradition holds that they were kinsmen, which is certainly possible given the small circle of Judah’s elite. When Josiah's ministers consulted Huldah in 622 about the newly discovered scroll, she gave a reply that was holy deuteronom-istic—that is, the Lord would bring disaster upon Israel because its people had followed other gods (2 Kgs 22:16–20). Jeremiah, of course, followed the same line and vigorously pushed the Josiah reforms. But a quarter century later, while still in Judah, the two held divergent views. Huldah wore the crown of queen mother and probably led in worshiping the queen of heaven. For his part, Jeremiah was prophesying against her and her practices. Later still, when Huldah and Jeremiah were in their fifties, the two old acquaintances were debating in Upper Egypt whether a woman could continue to honor the queen of heaven while remaining an adherent of Yahweh.

In his chapter 44, Jeremiah speaks to “all the Judeans living in the land of Egypt, at Migdol, at Tahpanhes [Jacob, Jozadak], at Memphis, and in the land of Pathros” (Jer 44:1). The exiles were scattered, and possibly their leadership was also. “Tahpanhes” has Jacob and Jozadak anagrams, and the account of the debate (Jer 44:15–30) at Pathros contains anagrams for Daniel, Asaiah, Ezra, and Jacob (again). The governing structure that the Judean exiles in Egypt used appears to be that of elders. Across Scripture as a whole, Huldah anagrams occur repeatedly in the word “elders”— twenty-two times, a frequency that cannot be coincidental. Flatly stated, this proves that Huldah served as one of the elders of the exilic community in Egypt (consider, too, that she had held the title of elder in Babylon fifteen years before when she visited Ezekiel).

The position of elders had a long tradition in the ANE and in Israel, too. “Elders are . . . grown-up men, powerful in themselves, by reason of personality, prowess, or stature, or influential as members of powerful families.” The expert sees elders as a constant in Israel’s life, “as prominent under the monarchy as they were before it.” One would expect the exiles in Egypt to continue their long-established practice of rule by elders. However, one would not expect that Huldah, a woman, would have become one of them. Of course, over twenty years earlier, she had briefly held the prestigious position of queen mother, and among exiles this must have carried weight. Nevertheless, it still would have required great force of personality to join that select circle of leaders.

When she arrived in Egypt, the prophetess would have been in her mid-fifties, and she probably remained in Egypt for about eleven years. It seems that Jehoiachin was with her, but we find no indication that he acted as a king-in-exile. Let his status remain unresolved.

Josephus writes that a Babylonian invasion of Egypt started five years after the final fall of Jerusalem, or about 581. Judean refugees in Egypt would certainly have fought against Nebuchadnezzar. The campaign must have concluded in a year or so, leaving the Judean settlements in Egypt with a cadre of experienced fighters. Using their Egyptian sanctuary, in the early 570s Baruch, Jacob, Ezra, Jozadak, Shaphan, Huldah, and others assembled funds and soldiers to retake Jerusalem. This writer has shown elsewhere how anagrams help to outline the extensive preparations made by the leaders of the Egyptian exiles.

It is time to update the table showing Huldah’s biography. So far, this chapter has discussed her exile to Babylon in 597, her return to Jerusalem in time for the 586 siege, and her subsequent flight to Egypt where, as an elder, she debated Jeremiah and made preparations to retake Jerusalem. By then, Huldah was in her sixties. Still to come was one of the Exile’s most important events—the Cyrus revolt, which will be discussed next. Table 4.1B shades the events in Huldah's life already covered.

| Year | Age | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 640 | Birth | |

| 622 | 18 | Consults on temple scroll |

| 615 | 25 | Marries Jehoiakim, bears Jehoiachin |

| 605 | 36 | Sees King Jehoiakim burn prophecy |

| 597 | 43 | Becomes queen mother |

| 597 | 43 | Exiled to Babylonia with Jehoiachin |

| 592 | 48 | As elder in Babylonia visits Ezekiel |

| 586 | 54 | In Jerusalem during siege |

| 586 | 54 | To Mizpah after Jerusalem’s fall |

| 585 | 55 | Gedaliah murdered, Huldah to Egypt |

| 575 | 65 | Cyrus revolt begins |

| 574 | 66 | Israelites take Jerusalem |

| 573 | 67 | Enemies retake Jerusalem, Huldah flees |

| 572 | 68 | Makes way to Bethel |

| 564 | 76 | Death |

In 577 or 576, the elders in Egypt reached out to Cyrus, then in his early twenties. The senior leadership must have come to agreement with him, for there is strong evidence that he met repeatedly with Huldah and Baruch and probably with other elders as well. Each of the twenty-two “elders” text words proving that Huldah held that office also contains anagrams for Baruch and Cyrus. Again, this cannot have been coincidental. Here is an example. The Lord tells Moses, “They will listen to your voice; and you and the elders [H, Baruch, Cyrus] of Israel shall go to the king of Egypt and say to him . . .” (Exod 3:18). While the elders—Huldah and Baruch among them—had authority, apparently they answered to Moses (who might have been Shaphan, King Josiah’s ex-Secretary). This Exodus example suggests that Cyrus was in Egypt during the organizational phase of the revolt. To assemble an army near Egypt would have necessitated negotiations with Pharaoh, and may also have meant battling the Egyptians to gain release.

The Israelite leaders could have made no better choice than Cyrus. Though young in the mid-570s, he was to become a great statesman and military commander. Thirty-five years after joining the Israelites in Egypt, Cyrus, at the head of his Persians, marched into Nebuchadnezzar’s fabled capital and took down the Babylonian Empire. Cyrus the Great ranks with Alexander, Genghis Kahn, Tamerlane, and Napoleon as history’s foremost conquerors.

575–572: IN LATER SIXTIES, HULDAH IN CYRUS REVOLT

Huldah accompanied Israel’s army north as it fought and defeated Judah’s former neighbors, who had seized the Exile to expand into Israel’s territory. Though the prophetess was in her later sixties, coded spelling shows that she played an active part in the campaign. The book of Joshua described the battles, and major sections of it were from her hand. By way of illustration, Huldah’s whimsical pen describes the battle of Jericho. The word for “trumpet” forms a Huldah anagram, and the account of Jericho’s fall has seven of them. For example, the Lord instructs Joshua, “On the seventh day you shall march around the city seven times, the priests blowing the trumpets [H]” (Josh 6:4). And what exile would fail to understand that Jericho’s mighty battlements also represented the massive double walls that Nebuchadnezzar had built to protect his Babylon?

In that same chapter, “The LORD said to Joshua, ‘See, I have handed Jericho over to you, along with its king and soldiers [H, Jehoiachin]’” (Josh 6:2). “Soldiers” shields anagrams for Huldah and for Jehoiachin, which means that her exiled son apparently was among the commanders of the liberating army. Joshua 6 also completes the tale of Rahab, the prostitute with whom Israel’s spies had earlier taken shelter when reconnoitering Jericho. The Rahab story, in both chapters 2 and 6 of Joshua, used the text word “spy,” which fittingly houses a Cyrus anagram (Cyrus later became famous for his use of subversion and espionage to further his military aims. He was to capture the capitals of both Lydia and Babylon without resorting to arms).

Joshua 10 is another chapter with numerous Huldah encodings. Two verses of poetry are especially noteworthy. The Lord “said in the sight of Israel, ‘Sun, stand still at Gibeon, and Moon, in the valley of Aijalon.’ And the sun stood still, and the moon stopped, until the nation took vengeance on their enemies” (Josh 10:12–13). This is a favorite theme of Huldah’s—the Lord’s use of heavenly bodies to intervene militantly on the side of Israel. Elsewhere, the Song of Deborah runs, “The stars fought from heaven, from their courses they fought against Sisera” (Judg 5:20), while Habakkuk has, “The moon stood still in its exalted place, at the light of your arrows speeding by, at the gleam of your flashing spear” (Hab 3:11). Huldah wrote each of these, enlisting the Lord on the side of his people. Perhaps she had in mind that the Babylonians sought to terrorize their captive subjects with the natural movements of the sun, moon, and planets. During the Exile of the Jews, there were eighty-one solar and lunar eclipses over Babylon. By calculation, about half of these resulted in the execution of a substitute king. Most victims, of course, were not Jews, but Ezekiel, Jehoiachin, Jehoiakim, and Zedekiah died in this fashion, and possibly Asaiah and other leaders did as well. Huldah would have known each one of these leaders personally. Also, both her own husband and her son died as substitute kings.

Was Huldah active as a warrior? In her long life she certainly had opportunity. She survived two Jerusalem sieges, one of them of several years’ duration. In the first she was in her forties, in the second in her fifties. During Nebuchadnezzar’s lengthy siege that ended in 586, women probably helped to “man” the city’s battlements—and if they did, Huldah would have led. When she was in her sixties, she accompanied the Israelite army as it fought its way northward toward Jerusalem in the course of the Cyrus-led revolt. During that time, Huldah undoubtedly witnessed—and perhaps directed— plenty of fighting.

The traces she has left in Scripture are fascinating. She invented (or revivified) the character of Deborah, the warlike heroine of the book of Judges. And even more importantly, numerous applications of the Hebrew words “warriors” and “mighty” form Huldah anagrams. For example, in the Song of Deborah, anagrams within “against the mighty” in Judg 5:13 and 23 alerted contemporary readers about both Huldah and her son King Jehoiachin. (It also alerts us that Huldah wrote the Deborah poetry in the 570s, during or immediately before the Cyrus revolt. This would have been the only time that Jehoiachin was available to lead in open fighting, as opposed to siege warfare.)

In some sixty passages, Scripture’s authors used the root for “warrior” to form a Huldah anagram. Close to half of these appear in Chronicles, and they are invariably favorable. For example, “They helped David against the band of raiders, for they were all warriors [H, Jehoiachin anagrams] and commanders in the army” (1 Chr 12:21). First Chronicles 7, 11, and 12 contain the bulk of these friendly anagrams, most of which are about David’s soldiers. One can conclude both that those chapters are about the revolt and that a portion of Chronicles was either by Huldah or one of her supporters.

A single passage in 1 Chronicles 5 illuminates the opposition that targeted Huldah and the mid-Exile revolt that she led: “ These were the heads of their clans . . . mighty [H, Jehoiachin] warriors, famous men . . . But they transgressed against the God of their ancestors, and prostituted themselves to the gods of the peoples of the land . . .” (1 Chr 5:24–25). Very likely, a later hand penned the insult that begins with “But they transgressed . . .” This is the only instance within Chronicles of a “warrior” anagram negative to Huldah—though it probably was a positive anagram that opponents converted to an insult.

The “warrior” anagram was used frequently in describing the conquest of the Promised Land during the Cyrus revolt. Here are several: “All the warriors [H, Jehoiachin] among you shall cross over armed before your kindred and shall help them”; “Joshua chose thirty thousand warriors [H, Jehoiachin] and sent them out by night”; and “ The LORD said to Joshua, ‘See, I have handed Jericho over to you, along with its king and soldiers [H, Jehoiachin]’” (Josh 1:14, 8:3, 6:2).

Virtually every prophetic book used the “warrior” anagram against Huldah. Generally, the prophets did this by painting mighty men as Israel’s enemies. For example, “ The heart of the warriors [H, Jehoiachin] of Edom in that day shall be like the heart of a woman in labor” (Jer 48:41). Note the added woman-in-labor touch. The Later Prophets contain close to twenty of these negative “warrior” anagrams.

The very best of the Huldah-warrior anagram passages is this poignant poetry, which has been previously quoted. Ostensibly, it is David’s death-dirge over Saul; instead, it might mourn the death of Huldah’s husband Jehoiakim. Huldah uses no statistically significant encodings of her name to sign this scripture. Rather, she relies entirely upon anagrams.

Your glory, O Israel, lies slain upon your high places! How the mighty [H, Jehoiachin] have fallen! Tell it not in Gath, proclaim [H] it not in the streets of Ashkelon; or the daughters of the Philistines will rejoice, the daughters of the uncircumcised [H] will exult. You mountains of Gilboa, let there be no dew or rain upon you, nor bounteous fields! For there the shield of the mighty [H, Jehoiachin] was defiled, the shield of Saul, anointed with oil no more. From the blood of the slain, from the fat of the mighty [H, Jehoia-chin], the bow of Jonathan did not turn back, nor the sword of Saul return empty . . . How the mighty [H, Jehoiachin] have fallen, and the weapons of war perished! (2 Sam 1:19–22, 27)

572: AT SIXTY-EIGHT, HULDAH FLEES WHEN REVOLT CRUSHED

April 28, 573 BCE is the last exact date that the book of Ezekiel provides. The chapter so dated launches the prophet’s blueprint for restoration of the temple, and it also opens with a Huldah anagram: “In the twenty- fifth year of our exile, at the beginning of the year, on the tenth [H] day of the month.... (Ezek 40:1). We think that this dates the battle marking Jerusalem’s recapture by enemies—either by Nebuchadnezzar or by an alliance of neighbors. Appropriately, Ezekiel laid out the dimensions of the new city in a chapter dated on the day, month, and year of the city’s most recent destruction. The anagrams are scarce, but the long (and not engaging) chapter is crammed with Jehoiachin coded spellings. Given the context, the spellings indicate that King Jehoiachin was captured at the Jerusalem site.

This line from Joel has the ring of an appeal to others for help as hostile armies approach: “Come quickly, all you nations all around, gather yourselves there. Bring down your warriors [H], O LORD” (Joel 3:11). “ Those who are swift of foot [H] shall not save themselves, nor shall those who ride horses save their lives,” reads an unsympathetic Amos 2:15. “ Their warriors [H] are beaten down . . . ‘Terror is all around!’” adds Jeremiah (Jer 46:5). Several of the Lamentations chapters surely came from this time, if only because they contain Cyrus ana-grams: “My priests and elders [H, Cyrus] perished in the city while seeking food to revive their strength” and “Lift your hands to him for the lives of your child-ren, who faint [H] for hunger . . . The young and the old [Cyrus] are lying on the ground in the streets; my young women and my young men have fallen by the sword” (Lam 1:19; 2:19, 21).

Isaiah 22 has within it an account of the battle “in the valley of vision [H]” (Isa 22:1). Most likely this was the 573 battle of Jerusalem. Indeed, the chapter’s first seven verses contain six Huldah anagrams. Like a newscaster, the author leads with this: “All your rulers [H] have fled together, without the bow they were captured. All of you who were found [H, Cyrus, Baruch] were captured, though they had fled far away” (Isa 22:3). Those “who were found” were captured, but we know that at least Huldah and Cyrus escaped. The reporter continued, “‘Let me weep bitter tears; do not labor to comfort me for the destruction of the beloved [RSV reads “daughter”] of my people’” (Isa 22:4). “ The daughter of my people” might refer to Huldah herself. The next few lines contained yet three more Huldah anagrams. She may have written this herself: “For the Lord GOD of hosts has a day of tumult and trampling and confusion in the valley of vision [H], a battering down of walls and a cry for help to the mountains. Elam bore the quiver with chariots and cavalry [H] . . . Your choicest valleys were full of chariots, and the cavalry [H] took their stand at the gates” (Isa 22:5–7). The chapter also contains the notable phrase “Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die” (Isa 22:13).

From Babylon, the prophet Ezekiel injected hope into the battle’s dismal outcome. God commands his prophet, “‘Breathe upon these slain [H, Jehoiachin], that they may live.’ I prophesied as he commanded me, and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood on their feet [Cyrus], a vast multitude” (Ezek 37:9–10). The aftermath of the Jerusalem battle is the proper context for this famous chapter about the valley of dry bones.

Slavery was the fate of those who escaped death: “I will send survivors to the nations, to the coastlands far away that have not heard of my fame or seen my glory; and they shall declare my glory among the nations [H]”; “ Though I scattered them among the nations, yet in far countries they shall remember [H, Jehoiachin] me, and they shall rear their children and return”; and “As for the people, he made slaves of them [H] from one end of Egypt to the other” (Isa 66:19, Zech 10:9, Gen 47:21).

Huldah herself evaded her enemies, but by the narrowest of margins. “My bones cling to my skin and to my flesh [H], and I have escaped [H, Ezra, Baruch, Cyrus] by the skin of my teeth” (Job 19:20). This reveals that Ezra (the author of the P Source material) and Baruch accompanied Huldah and that Cyrus also escaped with her. Previously, we had thought that the Persian deserted the rebel army before the final battle at Jerusalem.

Seemingly, Gen 19 is about the rescue of Lot and his family from the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. In actuality, the chapter tells of the escape of Huldah, Cyrus, and others from doomed Jerusalem. Genesis 19:2 packs three Cyrus anagrams into three text words. The rest of the chapter (vv 17–22) contains five Huldah anagrams hidden within the text words translated as “flee” and “escape.” The cover story for Huldah’s escape was about Lot. His situation was immediate and dire. An angel urged Lot, “‘Flee [H] for your life; do not look back or stop anywhere in the Plain; flee [H] to the hills, or else you will be consumed.’ And Lot said . . . ‘I cannot flee [H] to the hills, for fear the disaster will overtake me and I die. Look, that city is near enough . . . Let me escape [H] there . . . and my life will be saved!’” The angel then agrees to delay destruction of the cities and tells Lot, “Hurry, escape [H] there, for I can do nothing until you arrive there” (Gen 19:17–22). Zoar was the immediate destination of the fugitives. It lay at the southeastern edge of the Dead Sea depression. The Dead Sea is the lowest surface on earth, with severe heat in most seasons. Huldah’s flight to Zoar after the battle of Jerusalem probably took place early in May of 573. Interestingly, Scripture associates the settlement at the edge of the Dead Sea with Moab (Isa 15:5, Jer 48:4), and Huldah herself probably was of Moabite descent. She would have been sixty-eight years of age when she sought refuge there.

After fleeing to Zoar in 573, Huldah made her way northward to the vicinity of Bethel, which is some fifteen miles beyond Jerusalem. At Bethel, she lived and wrote for nine years, until her death in 564. that brings Huldah’s biography full circle, from 640 to 564.

Her son Jehoiachin probably was captured during the Jerusalem battle. It is likely that he spent the years from 573 to 561 imprisoned in Babylonia. In early April of 561, the authorities released him in order to crown him as a substitute king—which is contrary to the misleading account that ends the book of Second Kings. Jehoiachin died heroically after an extended hunger strike. As for Cyrus, he would have made his way north and east until he reached either the Medes (to whom he was royally connected) or his native Persia. Perhaps a guard of soldiers accompanied him and Huldah to Zoar, perhaps not. Until this sighting, historians have had no glimpse of Cyrus before 553 BCE, the date when the Persian allied himself with Babylon.

The last words of this biographical sketch belong to Huldah herself. Though Ps 31 is short, it has 102 Huldah-related spellings. (The probability of coincidence is 4.1 × 00000000000000000000001.) Several Cyrus anagrams testify that she composed the psalm in her final years.

Discovering Huldah also leads us to the Yom Kippur’s source. Leviticus 18, the basic text for Yom Kippur’s atonement, contains numerous Cyrus and Huldah anagrams. (Five Huldah anagrams were even fashioned from the word for “sin offering”.) Today’s deeply personal remembrance is surely founded upon guilt incurred from the tragic 573 slaughter at Jerusalem.